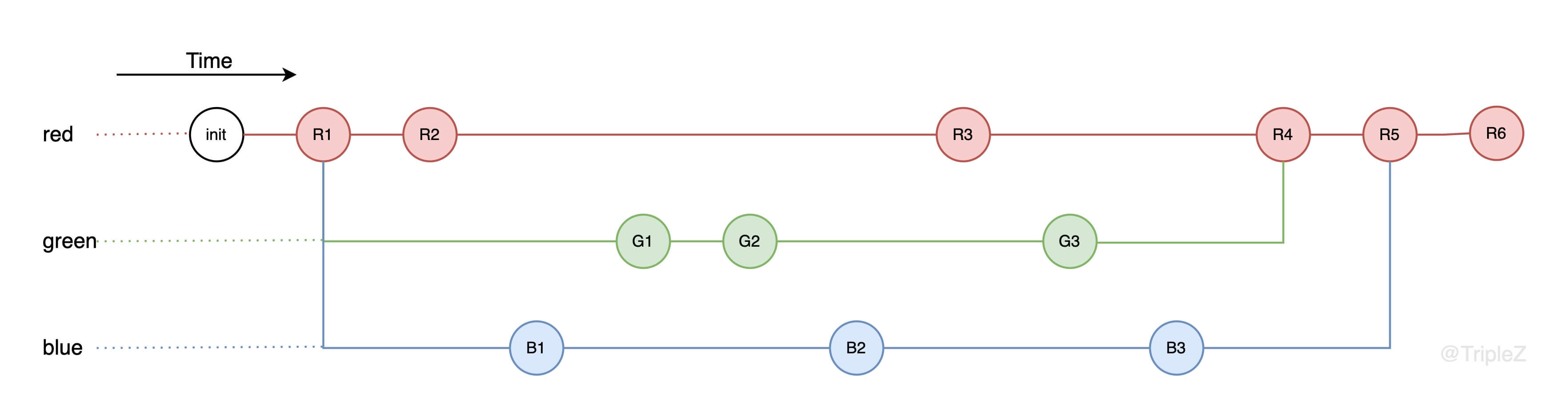

Everything in this article will be based on the following (carefully constructed) example, which covers most of the Git log patterns that tend to occur on projects.

The example scenario that runs through this article is this example’s chronological Git commit history.

|

|

Quickly create the example.

|

|

A diagram of the current Git commit history is shown below.

The basic principle of the Git cherry-pick command is to migrate commits to a target version based on the diff information in the commit that the user has selected. A typical application of this feature is to apply hotfixes to other LTS releases.

The general usage of git cherry-pick is as follows.

|

|

Here the <commit>... is the commit (set) that the user wants to port, which is the main point of this article.

<commit> can be either a single commit or a revision range. If it is a revision range, the command resolves all commits in that revision range into a single commit. cherry-pick can accept multiple <commit>s at the same time, which is similar to the -no-walk behavior in git rev-list.

So let’s explore the case where <commit>... is a single commit and revision range.

Single commit

Normal commit

Going back to the example above, if we only need to pick out G2, we can do this.

In this case, a merge conflict will occur and the output is shown below.

|

|

This tells us this information: the green file does not exist in the current (staged) version of HEAD, but it exists in the selected G2 commit. If you need the file, use git add to commit it to the staging area, or use git rm to discard the green file if you want to keep the current staging version in its current state, i.e. delete it.

We want to keep the green file after we select G2, so we do the following.

At this point the cherry-pick operation is complete. If you continue with git cherry-pick --continue, you will see error: no cherry-pick or revert in progress, which means that no cherry-pick task is currently in progress.

If you look at the current commit log, you will see that G2 is already on our current branch, cp-single-normal-commit.

Merge commit

What if we want to select a merge commit, for example, R4.

After executing this cherry-pick command, you will get the following output.

By default, cherry-pick does not handle merge commits and reports an error. This is because in a merge commit, there are multiple parents, and Git doesn’t know which parent to use as the mainline.

The error message also tells us that if you want to select a merge commit, you need to use the -m (or -mainline) option to specify which parent is the mainline.

With the git show command, you can get multiple parents of a merge commit, numbered from 1. Since the mainline parent we need to pick in this example is R3(17e2629), we choose -m 1 in cherry-pick.

Let’s try it again.

|

|

cherry-pick is done! If you look at the current commit record, you will see that a new R4 commit has been generated on the cp-single-merge-commit branch.

Now let’s go back to what just happened with -m 1. If you look at the files on the cp-single-merge-commit test branch now, you will see green and no red.

This is because when we pick the merge commit, we are using mainline 1, the red branch. So the fact that cherry-pick is based on red and is looking for differences between the mainline 2 green branch and red, the changes made on the green branch are the ones selected.

Revision range

There are several ways to represent a revision in Git, but here we’ll focus on the revision range.

For revision range, there are six ways to represent it.

-

^<rev>: denotes exclusion of<rev>and all its reachable parent commits. -

<r1>..<r2>: equivalent to^r1 r2, i.e. includes<r2>and its reachable parent commit, and excludes<r1>and its reachable parent commit.If you need to include

<r1>, you can use this writing style:<r1>^..<r2>. -

<r1>..<r2>: includes all<r1>or<r2>and their reachable parent commits, and excludes the common parent commits reachable by both<r1>and<r2>. -

<rev>^@: includes all parents of<rev>, but excludes<rev>itself. -

<rev>^!: includes<rev>itself, but excludes all parents of<rev>. That is, it indicates a single<rev>commit.Note:

<rev>(for<rev>and all its parents) is different in the context of revision range than<rev>^!. Both are considered identical only if the--no-walkargument is specified (both denote only<rev>itself). -

<rev>^-[<n>]: Includes<rev>and all its parents, but excludes the<n>th parent of<rev>and all its reachable parents. The default value of<n>is 1.

It seems complicated, so let’s use the scenario in the text to give two examples of range representations.

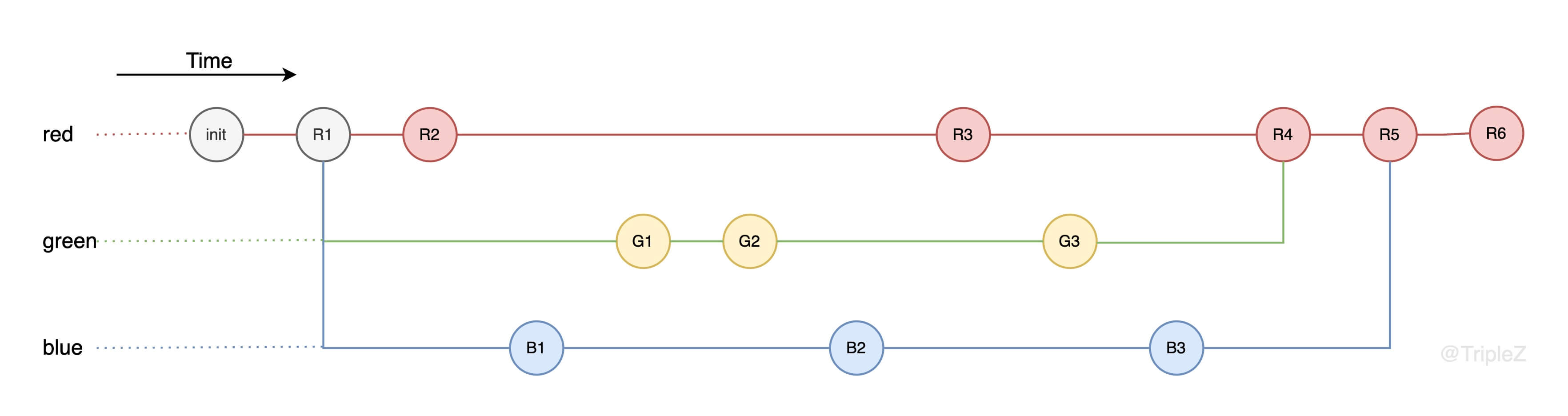

First, consider the case where <r1> and <r2> are both on the same branch, such as G1 (05719c8) and G3 (c950910).

The meaning of 05719c8(G1)^. .c950910(G3) should mean.

- includes

G3and all of its parents. - and excludes all parents of

G1(does not excludeG1).

The result should therefore be a selection of all commits from G1 to G3, schematically shown below, with the included nodes in yellow and the excluded nodes in gray.

Let’s take a look at the current commits.

Bingo! The three commits G1, G2 and G3 have been selected.

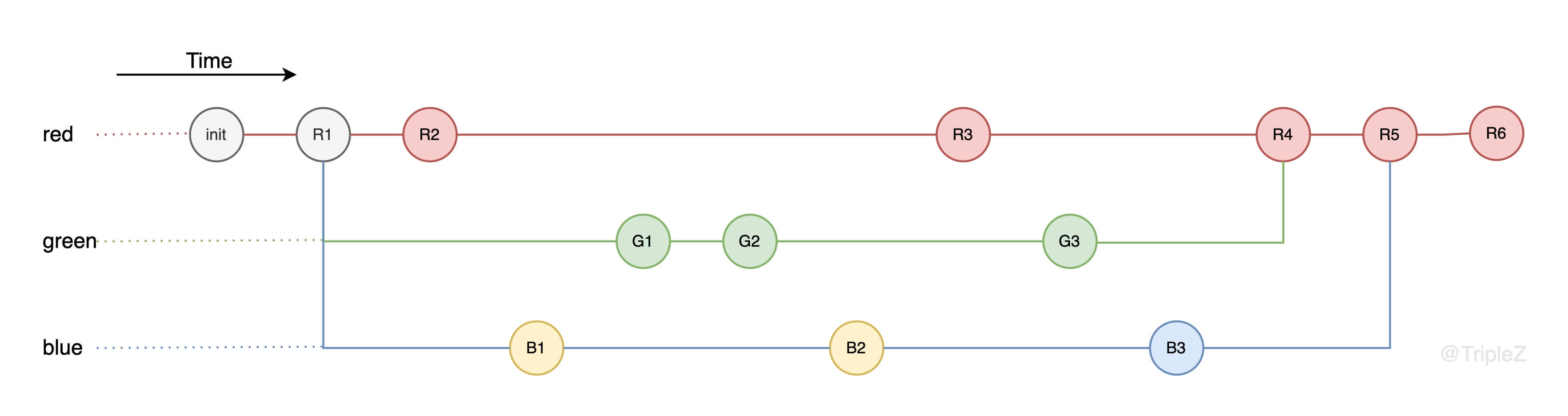

What about <r1> and <r2> on different branches?

Let’s take G1 (05719c8) and B2 (69edfc9) as use cases.

The meaning of 05719c8(G1)^. .69edfc9(B2) should mean.

- includes

B2and all its parents. - and excludes all parents of

G1(does not excludeG1).

Since B2 and all of its parents do not include G1. Therefore we can interpret G1^. B2 as the result of including B2 and all its parents, and excluding the common parent of B2 and G1. Naturally, only B1 and B2 are left as commits. The diagram is as follows, with the included nodes in yellow and the excluded nodes in gray.

Let’s look at the current commit record again, and indeed only two commits are selected, B1 and B2.

Rerere

Rerere is “reuse recorded resolution”, which is a method to simplify conflict resolution.

If you do a lot of merge, rebase or cherry-pick, or are maintaining a branch that is different from the trunk for a long time, it is highly recommended to enable the rerere feature.

Enabling rerere is very simple and requires only one global configuration.

|

|

You can also create a .git/rr-cache folder directly in your local repository to enable rerere for that repository.

What’s next

In the process of writing this article, I also came across the series of Stop cherry-picking, start merging articles written by Raymond Chen of Microsoft, in which he mentions the pitfall that cherry-picking may cause in many engineering practices. In the following time, I will read the series of articles one by one and analyze whether cherry-picking can bring us enough benefits in common software development workflows and whether we should stop cherry-picking, start merging according to the cases in the articles.