TypeScript is a superset of JavaScript that brings static type support to JS, which can help us write clearer and more reliable interfaces and bring better IDE hints. It’s been a while since I’ve used TypeScript with React in a front-end project, and it’s time to write a blog summary to share. The following is a list of some points that I personally find helpful in doing projects.

Using automatic inference

TypeScript has some ability to infer types, which in some cases allows programmers to be lazy and write fewer types.

When passing an arrow function to component props, the arrow function does not need to be typed if the props have a type.

Also, don’t forget that functions in TS/JS are first class citizens, for example, if you need to write a function to separate numbers by three digits, you may find that there is an Intl module that can help.

Tool types

If there are some third-party components referenced in the project that have some common attributes across all uses, such as <Input type="number" ... />, all types have to be fixed to number, and we generally have to extract a component out.

This is essentially writing a biased function, but if the referenced third-party library has a complete type declaration, writing it this way rewrites the original type of the third-party library and can save code by declaring the component props type this way.

Omit is a TS tool type that does exactly what its name suggests, it takes some attributes out of a type. In the above example, the use of Omit avoids duplicate declarations of existing third-party types. TS also has a number of useful tool types, such as Pick which extracts some properties from existing types to form new types, NonNullable to remove null and undefined, Parameters and ReturnType to get the types of function parameters and return values, etc., which can be used flexibly as needed.

Introduce some ambiguity where appropriate

Explicit is better than implicit.

The above quote is from The Zen of Python, but what exactly is explicit and what is implicit? Take Ant Design Pro for example, which provides a way to inject global variables.

It’s fine if all the developers on the team are familiar with this feature, but if a new member of the team joins the team and sees that the code somewhere uses this global variable and the IDE can’t jump to the definition, the mind will be full of doubts. I prefer to explicitly declare what I want to introduce where I need it.

However, there are some tolerable ambiguities in TypeScript.

declare global declarations

In the early days of TypeScript, when many popular libraries used only JavaScript without type declarations, there were type definition files with the “d.ts” suffix that could add types to JS code.

TS itself comes with some declaration files, such as the declaration of the browser global object window.

This can also be used to declare types for your own code, and I’m used to using it in the following way.

Although there is no explicit import, the jump definition of the IDE works fine, and since it is only a type definition, it does not generate unexpected runtime errors, eliminating an import statement I think is more beneficial than harmful. You can encapsulate all the interface response values in a module, and if you use a tool like OpenAPI on the backend, you can also use some plugins like openapi-typescript to directly export a type file for the interface. exporting a type file.

Declaring merge

I’m usually more comfortable declaring types with type, but sometimes a more “dirty” feature of interface can come in handy.

This feature of interface, together with the module augmentation feature, can help library developers to provide better extensibility to users. For example MUI to customize the theme configuration.

|

|

This expands the original type definition of the MUI, and neutral becomes a legal color value.

Type of useRef

useRef is described in React’s documentation as.

useRef returns a mutable ref object whose .current property is initialized to the passed in parameter (initialValue). The returned ref object persists throughout the component’s lifecycle.

useRef or createRef is often misunderstood as being used to get the DOM node of a child component, but in fact its argument can be any object, and since the ref object returned by useRef still holds a reference to the same object even if the component is re-rendered, it can be used to handle some complex closure scenarios.

When TypeScript is combined with useRef, if you try to assign a value to the current of the object it returns, you sometimes get an incomprehensible type error: Cannot assign to current because it is a read-only. This is strange, why is current immutable?

It is worth mentioning that React itself has type checking in the development environment, but instead of TypeScript, Facebook’s own FlowJS is used. Check out useRef’s source code, its type is a normal generic function: T => { current: T }, but we use TypeScript to do static type checking when developing React applications, and actually rely on the @types/react library, and looking at the source code, we can see that here useRef does use the overload.

As you can probably tell from the type name, if the return value is MutableRefObject<T> it should not report an error, and it does. The current property inside RefObject is readonly. To avoid this error, you can use useRef like this.

|

|

If you use useRef<sometype>(null), then sometype matches the generic type T, the argument matches T | null, and the whole call matches useRef<T>(initialValue: T | null): RefObject<T>, while if you use useRef<sometype | null>(null), then the union type sometype | null matches the generic parameter T, the parameter initialValue is also of type T, and the function call matches useRef<T>(initialValue: T): MutableRefObject<T> . In the Rust community, we sometimes call this “type-levelling “, and it’s a bit like leveling a chemical equation :)

Off-topic : This issue contains a discussion of why @types/react is labeled useRef types the way it is.

Type Narrowing and Conditional Rendering

The term type narrowing may not be very common, but it is likely that you have used it without realizing it, and the most common would be a non-empty judgment like this.

The original type of data is string[] | undefined, which is a union type, but when it enters the if branch, the type of data is just undefined, which becomes “narrow”, and since return is eventually used in this branch, when it leaves the After leaving this branch, the type of data becomes string[] and you can safely use the map method. Type narrowing is often intuitive, for example, in the above example, if the program is executed in the if (!data) branch, then data must not be of type string[]; similarly, if you enter the if branch and then return, then if data is undefined, no subsequent code will be executed If data is undefined, then if data is string[], the code must not be executed after if, and vice versa. Operations like instanceof, in, switch, etc. can shrink types from broader to narrower ones. Also, if there is no return in the if branch, then the type of data is only narrowed within the if block, and it is not safe to use map later, where only return returns the function to eliminate the possibility of subsequent data types being null. branch to narrow the type of data after the branch.

Even if you use JavaScript to determine whether it is null or not, the type narrowing of TypeScript still brings some benefits, first of all, it ensures static type checking and cannot use methods that are not available on the current type, while In the example, the last data type is inferred as string[], the IDE can automatically complete the related map method, and the callback function parameter item of map will be inferred as string type accordingly, so you can use startWith and other prototype methods on it.

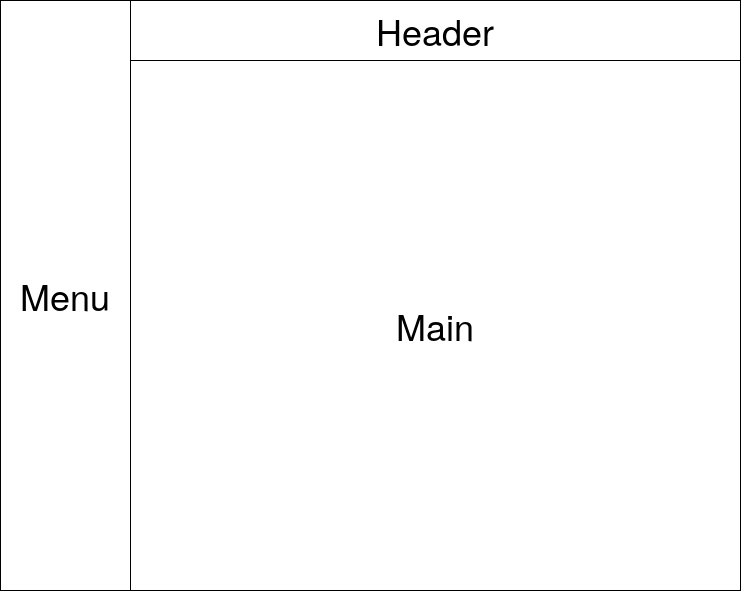

Next, let’s look at an example that is closer to the real project code. There is a backend application for a rental system, with a fixed page layout as shown in the figure.

But in the business process, there are three login roles, Admin, Landlord, and Tenant, and it stands to reason that these three roles do not see the same UI details after logging into the backend.

|

|

How easy is it to render different content according to different roles in the front-end? You can add a tag for each role type.

|

|

Here role is not a string type, but a literal type, and in the switch statement, such an additional field helps us narrow the User type to a more specific type, thus changing the rendering of the component based on the role.

At the end I used a const exhausted: never = user, which is a little trick to implement mutually exclusive parameters with never. never is a bottom type in TS, which to save space means that no value can be assigned to never except for never itself, and since all the previous cases already cover all possible cases of user and all have return, the code inside default will not be where the type of user is narrowed to never, and the assignment is then legal. But if someone adds a new role type CustomerService to the union type User, user cannot be narrowed to type never, and a type error is generated, suggesting that a case needs to be added to the switch statement to include all cases. This achieves exhaustive checking.

How to solve too much conditional rendering

If there is a lot of this code in the project

|

|

Such code, when maintained by multiple people, is likely to have more and more repeated judgments and nested judgments, which can be a headache to read and an even bigger headache to maintain. If there are a lot of conditional rendering in a project, how to keep the code tidy?

Component factory?

Combination?

There may be times when we don’t need to determine state everywhere, such as this user role issue, and can bind this state to a route that splits the page component into many widgets.

|

|

In the routing component we will render different page components depending on the role, the similarities in these components can be extracted to a common container and the differences passed through props, some elements unique to the page can be defined as optional properties, undefined and null are both legal JSX elements but will not be rendered. I personally prefer this declarative style of writing.