There are three principles of Rust Ownership to keep in mind.

- For each value, there is an owner.

- There can only be one owner for a value at a time.

- When the owner leaves the scope, the corresponding value is automatically dropped.

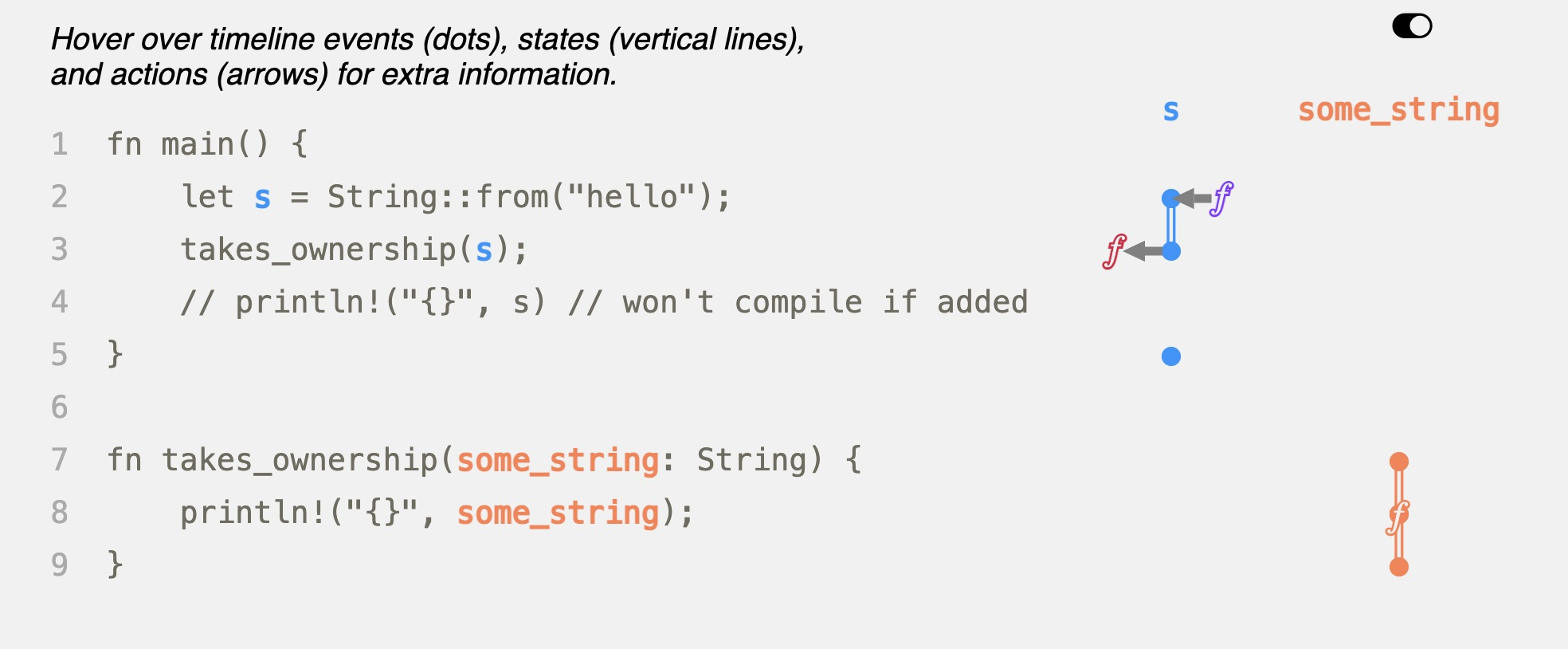

hello is a string allocated on the heap, and the owner is s, which, when passed as an argument to the function takes_ownership, moves ownership to some_string . That is, the hello string will be dropped when the function returns, so main will report an error if it prints line 4 because it has been moved.

What if main wants to continue printing hello? takes_ownership can return hello out, so the owner will move again to s . But it’s really inconvenient.

Introduction to references

This is where references come in, not moving ownership, just lending data.

The final runs all print, but no_takes_ownership does not own the owner, and &str represents a read-only reference to the string. no_takes_ownership(&s) , where instead of writing s directly, it takes a reference to &s.

Pointer and reference

The above is the simplest example of a reference, where a is an int32 type with value 0. Then _r is a reference to a.

|

|

You can see that the a variable is assigned on the stack rsp + 0x4, with an initial value of 0, and then line 3 is disassembled to show that lea takes the address of a and passes it to _r on the stack.

Essentially, a rust reference is not much different from a normal pointer, but at the compilation stage, various rules are added, such as the reference cannot be null.

Borrowing rules

reference (reference) does not acquire ownership, insisting on a single owner and single responsibility, solving the shared access barrier.

Passing objects by reference is called borrow, which is more efficient than transferring ownership.

- The lifetime of a reference must not exceed the time it is referenced. This is obvious, to prevent dangling references.

- If there is a mutable borrow of a value, then no other references (read or write) are allowed within the scope of that borrow.

- In the absence of mutable borrowing, multiple immutable borrowings of the same value are allowed.

|

|

This example will report an error for the obvious reason that y has to refer to the variable x, but x is in the statement block {} and becomes invalid when it leaves this lexical scope, so y becomes a dangling null reference.

|

|

In the above code, a_ref is a mutable borrow, and then a_ref.push is called to modify the string, while the original owner a is printed in number 4, and then an error is reported.

The reason for this is that a_ref is a mutable borrow and no other immutable or mutable borrow is allowed in its scope, where println! is an immutable borrow of a.

What confused me at first was how big the scope was! The ancient version was lexical scope, but it was improved to start with the first borrow and end with the last call, so the scope is much smaller.

After modification, just put println after push.

Confusing points

A structure can also have references in it, and it’s easy to get confused at first.

In this case Name is a string reference, so the instantiated Stu object does not have ownership of Name, so it has to conform to the borrowing rules above. To be clear, it is a question of who is responsible for releasing the content.

There is also a type of method, the first parameter should be written as &self or &mut self , if written as self then the function will capture the ownership of the type, the function is executed once, it can no longer use the type.

The above code is simple, the Number type has a get_num method to get the value of the variable num, but main will report an error when compiled if println is called twice.

|

|

You can see that the compiler gives hints, because get_num(self) defined as self will take ownership, which moves num.

So the first argument of the type method has to be a reference, and Go writers are sure to be confused. Similarly there is the match statement block, which also moves the image and requires a reference.