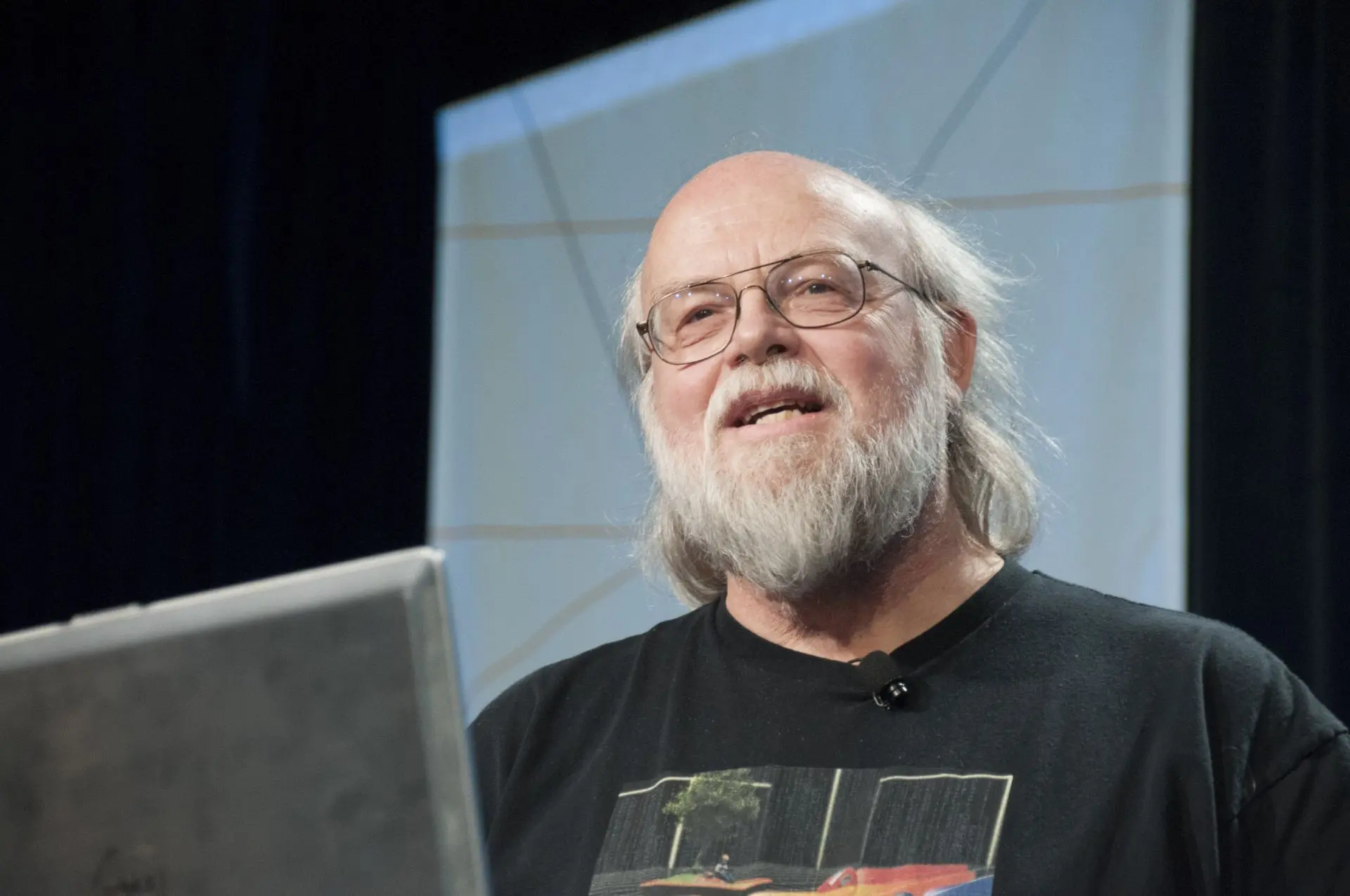

James Gosling, the Canadian computer scientist who did the original design of Java and implemented the compiler and virtual machine for the original version of Java, is also widely regarded as the ‘father of Java’.

James Gosling was recently interviewed by Grigory Petrov, a technical evangelist (DevRel) at Evrone, an enterprise software development company.

In this interview James Gosling talks a lot about programming languages, such as his views on the new features of modern programming languages, how he feels about the disruptive changes caused by updates to programming languages, why not all programming languages use JIT techniques and much more.

Grigory: We want to organise the Python, Ruby, Java and Go communities in Russia as software developers and software consultants. With this interview, I hope to show the basic problems of this industry and in turn help fellow developers. Your experience and work experience in Java can help developers become better, so let’s try to accomplish this together!

Some programming languages, such as Go, eschew classes and inheritance as features. As a language designer, what do you think is a modern, generic, logical way of composing programming languages?

James: I should continue to use classes, as I have found them to be very effective for this scenario. In fact, I don’t have any good, clear ideas about how to do things differently. The existence of macros in C is almost a disaster because they are not part of the language, but a feature outside of it. rust is exactly the kind of language that wants to use macros in the right way.

For other programming languages, such as the Lisp family, they have a way of defining syntax that is almost completely independent of semantics. I have written a lot of Lisp and am addicted to the technique of manipulating Lisp programs with Lisp programs. Some languages allow you to do this in a different way, like Groovy, where we can use ASTs directly, and Rust, which has syntax-integrated macros.

Lisp generates new code by manipulating code fragments, and this is often used in the Java domain. It’s a very low-level approach, but it’s very popular. Because developers can combine annotations and use different languages to generate bytecode, this is a very powerful technique that is often used in unexpected scenarios. An example is the Jackson framework, which boosts performance by computing serialisers.

Of course, this is both a powerful technique, but also very difficult to navigate. The technology is full of possibilities, but the possibilities are limited. I have a strong love-hate relationship with Lombok. It adds a lot of great Java features, but on the other hand, it also reveals its weaknesses. Some of the features are supposed to be built-in.

Grigory: We recently spoke to Ruby author Yukihiro Matsumoto, who mentioned an experiment he had done with the latest major release of Ruby 3.0. He tried to release this version without introducing breaking changes and see what happened. I know that Java is wary of ‘disruptive’. So is it a good idea for all programming languages to consider compatibility and for every major version to be compatible? Or is this only the case for specific languages like Ruby or Java?

James: It depends almost entirely on the size of the developer community. Every major change can cause problems for developers, and if the community is small then disruptive changes are not a big problem. There is also a cost benefit that must be weighed. If adding a disruptive change adds a burden, but at the same time brings some benefits, then it may be considered. For example, if the subscript operator is changed from square brackets to round brackets, it may not bring any benefit and will cause great distress to the developer. Then it would be a silly change.

As an example, JDK 9 introduces an extremely rare and destructive change: if a developer uses some so-called hidden API, the wrapper mechanism is disrupted, and developers who break wrapper boundaries and use APIs in ways they shouldn’t will run into a lot of problems upgrading from 8 to 9.

There is also the case when there is a bug somewhere and the developer has implemented a workaround for that bug. In this case, if the bug is fixed, then there is a risk that the workaround will be broken.

Grigory: Let’s talk about the development of companies and industries. I’ve never programmed a robot myself, but I spent some time working for companies that create software for millions of people. Comparing today with 20-25 years ago, I see that social coding platforms like GitHub are supported by giant companies that help individual developers and enterprise or industrial software developers to develop open source. So can we consider this a golden age for open source software, what do you think?

James: I don’t know how to answer this question as it relates to the future. The idea that “this is the golden age of open source software” implies that “it’s not going to be a downhill slide from now on”. If it’s a golden age now, then isn’t it a golden age in the future?

So my view is that whatever the golden age looks like, the environment we are in is getting better and better, and we are getting closer to the ideal ‘golden age’. At the moment, we are facing various crises around security and human cyber terrorism. While this is still happening or is happening, I don’t think this is the golden age. If there is some way to end cyber-terrorism - it will be a very ‘golden’ time, let’s wait and see. I would say it’s a really great time, but it can get better.

Grigory: You use the JIT technique in Java and the JVM. the JIT brings very impressive speed and does not affect the elegant syntax and high-level features of the language. Many programming languages refer to Java, such as C# and JavaScript, which recompile code with hot-path compilation at speeds close to those of C and C++. However, many other languages, such as Python, Ruby and PHP, have optional JIT but are not as popular. Many mainstream programming languages also do not use JIT to improve performance. So why don’t all programming languages use JIT to provide developers with faster speeds?

James: In fact, statically typed languages are better suited to JIT for performance. With dynamic languages, like Python, it’s actually very hard. What people usually end up doing is adding annotations to the language, and that gives you a programming language like TypeScript, which is essentially JavaScript with type annotations, which is interesting because JavaScript is essentially Java without the type declarations, so TypeScript is essentially Java with a hybrid syntax.

But if you’re a developer who’s writing fast scripts in Python, declarations seem to bother them, and thinking about the types of variables is very annoying. Most developers in the scripting language world don’t care about performance. They care more about getting their development done as fast as possible, and don’t care about performance and the associated details.

Grigory: There is a non-technical question. When we talk about different languages, in your personal opinion, what should be the first language for a developer just starting out or a student in a related discipline to choose as the first language they learn?

James: I’m definitely a little biased in my answer to this question, after all Java has been used successfully for so many years. But the first programming language I learned myself was PDP-8 assembly code, and around the same time I also learned Fortran. so I think for beginners, you can teach them anything, as everyone has different learning abilities.

However, in this case I think it is important to think more about the future career path of the beginner. If one wants to be a well-rounded software developer building a large, high-performance system, then there is no getting around the JVM language, regardless of what JVM language one learns. But if you’re a physics student, I’d say Python is good too.

In fact, I don’t think it’s a big deal which programming language you choose as your first language to learn. While many people will always stick with the first language they learn, it’s actually better if they can learn multiple languages and switch back and forth. I even think universities should offer courses that compare the advantages and disadvantages of programming languages. A course that involves completing assignments in 5 different programming languages would be designed to allow students to learn these languages quickly, as they are not really that different. But in this way the students think about the advantages and disadvantages of the languages.

I’ve done this a long time ago, for example with Cobol for numerical calculations and Fortran for symbolic operations, neither of which is an area of expertise for either language, but I still got an A in the end.