goroutine case

In our daily work, we often have code that starts a goroutine using the go keyword.

A first-time goroutine developer may think it’s over, but after running for a while, he may run into some problems and struggle to figure out…

For example, when a task in the goroutine runs too long, or gets stuck… It will keep blocking in the system and become a goroutine leak, or indirectly cause a resource spike, which will cause many problems.

How to stop the goroutine becomes a must-have skill, and only by mastering this skill can you use the goroutine well.

Close channel

The first method is to use the channel’s close mechanism to accomplish precise control of the goroutine.

In Go’s channel language, there are two ways for a channel to accept data.

These two methods correspond to different runtime methods, and we can use their second parameter to discriminate and jump out when the channel is closed, based on its return result.

Alternatively, we can take advantage of the for range feature.

It is a common use to loop through the channel ch until it is closed.

Periodic polling channel

The second approach, which is more refined, combines the first approach with a semaphore-like processing.

|

|

In the above code, we declared the variable done, of type channel, to be used as a semaphore to handle the closing of the goroutine.

The closing of a goroutine is not known, so in Go we use for-loop in combination with the select keyword to listen, and then call the close method to formally close the channel after the relevant business processing is done.

If the logic of the program is more structured, you can also not call the close method, because the goroutine will end naturally, so you don’t need to close it manually.

Use the context

The third way to do goroutine control and shutdown is to use the Go language context.

|

|

In context, we can get a read-only channel, of type struct, with the help of ctx.Done. This can be used to identify whether the current channel has been closed, either because it has expired or because it has been cancelled.

So context has its own flexibility for cross-goroutine control, either by calling context.WithTimeout to control it based on time, or by actively calling the cancel method itself to close it manually.

Kill the other goroutine

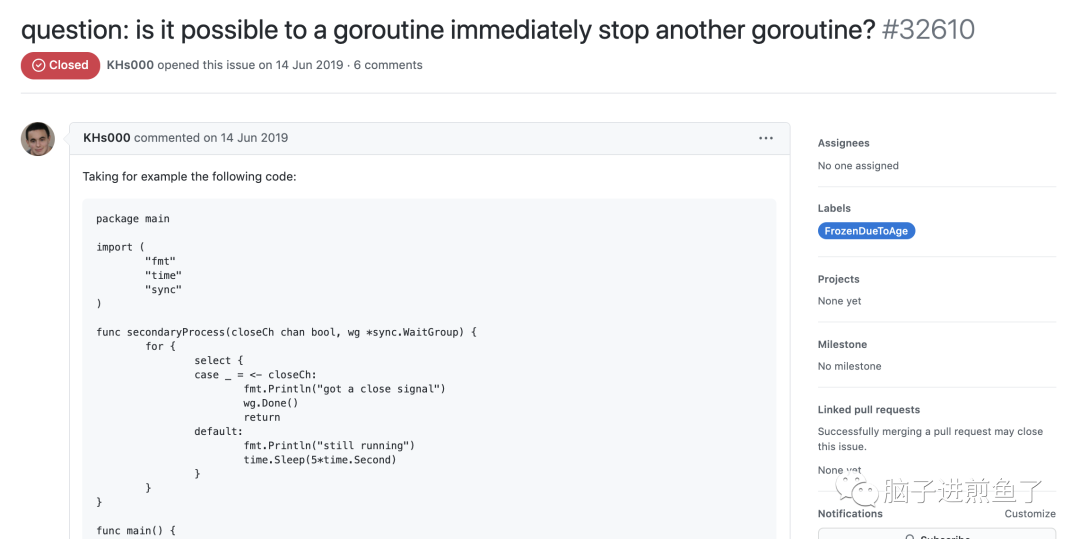

After learning about the 3 classic ways to stop a goroutine, some of you have come up with a new idea. It was “I want to stop goroutineB in goroutineA, is there a way?”

The answer is no, because in Go language, goroutine can only exit of its own accord, usually through a channel, and cannot be shut down or killed by other goroutines in the outside world, and there is no explicit concept of goroutine handle.

A similar question was asked in Go issues, and Dave Cheney gave some thoughts.

-

If a goroutine is forcibly stopped, what happens to the resources it has? Is the stack unstacked, and is defer executed?

-

If defer is executed, the goroutine may continue to live indefinitely.

-

If defer is not executed, the original application system design logic of the goroutine will be broken, which certainly does not make sense.

-

-

If you allow to force stop the goroutine, do you want to release everything, or just kick it out of the scheduler, and what problem do you want to solve with this?

It’s all worth thinking about, plus once you let go of such restrictions. As a programmer, you maintain code. It is very likely that you will not know where the handle of the goroutine was passed to, and when and where it was somehow closed, very bad…

Summary

Remember, it is a basic principle that every goroutine in the Go language needs to own up to any responsibility it has.

Reference https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/tN8Q1GRmphZyAuaHrkYFEg